Adjustable gas blocks. Buffer weights. Springs. Fractions of ounces cut from a BCG. Suppressed or unsuppressed. Barrel length. Profile too? Sub or super. All the puzzle pieces that answer the question: “Will it run?”

The reason for adding a .300 Blackout short-barreled rifle or AR pistol to the safe will vary from person to person. Perhaps it’s the best personal-defense option for one’s living space and property. Maybe it’s the perfect hush-hush guide gun during whitetail season, when it might be necessary to track a wounded deer through parcels peppered with wild hogs. Or, maybe, “just because” — which is never a bad reason.

The truth is with every inch subtracted from the barrel of a rifle chambered in .300 Blackout, the more difficult it becomes to get the gun to function reliably with certain ammunition. We’d argue the trouble is more exponential than linear, meaning the number of requisite adjustments increases with each inch lost.

While a 16-inch setup may only require an adjustable gas block so not to over-gas the rifle when shooting supers suppressed, a 7.5-inch rig may require a lighter BCG (bolt-carrier group), lighter buffer, lighter spring, and a can that delivers a healthy dose of back pressure.

Is it possible to find a factory load or create one’s own recipe that will work and stick with it — and only it? More than likely, yes, but why settle for just one when everyone knows variety is the spice of life? Plus, applications for one rig may need to vary.

When it comes to a .300 Blackout SBR or AR pistol, in regard to ammo choice, flexible is what we prefer, and we got downright fastidious to determine how best to get there.

Dwell time is the amount of time gas is acting on the BCG before the bullet exits the barrel. Most .300 Blackout rifles, regardless of barrel length, come equipped with a pistol-length gas block so to maximize dwell time. More dwell time, put simply, means more gas pressure, for a longer time period on the bolt. More often than not, .300 Blackout SBRs or AR pistols, if not flawlessly gassed, tend to run on the under-gassed side, especially when shooting subsonic ammo, which is loaded with a smaller powder charge and therefore produces less gas.

Not enough gas is often the issue for a .300 Blackout rifle or pistol that won’t cycle. But without adjusting the load itself, how can we compensate for less gas (or less pressure on the BCG) in order to get the firearm to cycle reliably? We did some testing to get closer to the answer.

To determine what components have the most influence on functionality across various .300 Blackout loads, we focused on two setups: an Aero Precision 10-inch government-profile barrel and a 7.5-inch Faxon Match barrel, both with an Aero Precision adjustable low-profile gas block and pistol-length gas tube. A Radian Weapons Raptor charging handle was incorporated for both.

We swapped out or adjusted the gas restriction, BCG, buffer weight, buffer spring, and suppressor.

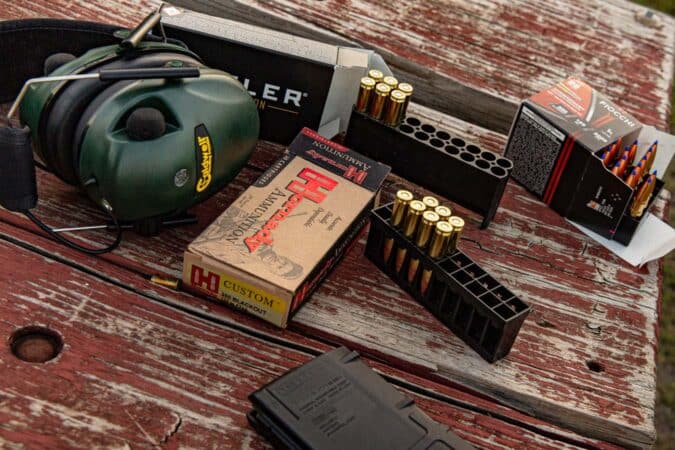

What ammo did we test? Two different subsonic loads: AAC 220-grain OTM (1,000 fps listed on box) and Nosler 220-grain Custom Competition JHP (1020 fps); two different supersonic loads: Fiocchi Extrema 125-grain Hornady SST Polymer Tip (2,200 fps) and Hornady Custom 135-grain Hornady FTX Polymer Tip (2,085 fps).

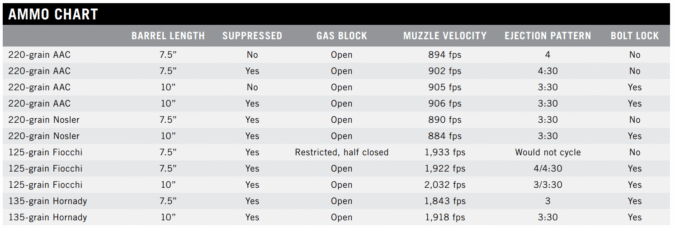

In the chart below, the muzzle velocity was tracked by Garmin’s Pro Xero C1 Chronograph, with the feet per second provided being an average of five shots.

Also included is our observation of ejection pattern as it relates to the hands on a clock. The ideal ejection pattern should fall between 3 and 4 o’clock. Closer to 5, and the gun is under-gassed and may not cycle and/or chamber the next round. Closer to 2 or 1, the gun is over-gassed and may result in a failure-to-extract and/or double feed, not to mention increased overall wear-and-tear on internals.

A bolt locking back on the final round (with magazine still inserted) is a sign that the rifle is properly tuned in terms of gas. For this reason, even though some loads would cycle round-to-round and eject occasionally close to 3 o’clock, the litmus test was a locking bolt, which would indicate the BCG reliably traveled the requisite distance to engage the bolt catch.

Standard carbine buffers were employed for the above data, though the BCG was swapped between a Radian Weapons BCG (11.5 ounces) and a Faxon Lightweight (8.5 ounces) with little discernible effect. Suppressors were removed and interchanged between SilencerCo’s Velos 7.62, Scythe STM (short and long config), and Sycthe-Ti.

While we thought it might be necessary to restrict gas with some supersonic loads, it became quickly apparent an open gas port worked best for both barrels across all loads.

For the suppressors initially threaded on, due to their large internal volume, the rifles may as well have not been suppressed — there was minimal backpressure to assist with cycling the BCG.

While initially there appeared to be little to no difference, in terms of cycling, between the Radian Weapons BCG and the lightweight Faxon option, once the standard carbine buffer was swapped for the Odin Lite, we started to see some synergy.

The whole concept for this article started with a group of colleagues asking the question, “But why not?” What can’t a .300 Blackout SBR at 7.5- or 8.5-inch cycle subs both suppressed and not suppressed? True, there’d really be no reason to run subs unsuppressed but that doesn’t stop us from asking why not.

It may not make sense. But science sometimes just doesn’t make sense.

The conclusion became if a .300 Blackout SBR or AR pistol setup could cycle subs unsuppressed, it could run any load.

Inside the Odin Lite buffer tube, we opted for three aluminum weights, each weighing 0.21 ounces. For context, three of these (that fill the tube) are equal to one steel weight (at 0.63 ounces). The standard carbine buffer contains weights a total of 1.89 ounces for the three, which totals out at approximately 3 ounces with the tube casing itself.

Other users of the Odin Lite have pointed out how the set screw may come loose after firing several rounds. We don’t doubt this — though we didn’t see it. A roll-pin system to secure buffer weights is more reliable and the common method with other buffers. Also, the two set screws on the Odin Lite tube — which we suspect were used for ease of swapping weights — add overall weight. Bottom line: Three aluminum weights installed inside a standard tube (that uses a roll pin) is preferred both for purposes of overall weight and not coming loose. For example, a standard carbine buffer than runs aluminum weights will weigh 1.75 ounces, approximately, versus the 2.15 ounces of the Odin Lite with aluminum weights.

As mentioned earlier, the swap to an aluminum-stuffed buffer, coupled with Faxon’s Lightweight BCG (8.5 ounces) is where we started to see progress, as subs would cycle and lock the bolt even when not suppressed (though, admittedly, not consistently).

A suppressor with limited internal volume will create blowback, which translates to a delayed pressure drop and residual gas acting on the BCG. While threading on a suppressor will not increase the peak gas-port pressure, it can increase effective dwell time.

As 3D printing becomes more of a thing for suppressors and manufacturers continue to innovate, “flow-through” designs and other configurations that present minimal blowback are becoming more prevalent. There are indeed advantages to this, especially on rifles chambered in 5.56, but bear in mind these styles of suppressors will not assist with cycling a .300 Blackout rig. As mentioned before, with some of these larger-internal-volume suppressors equipped, it’s almost like running the gun unsuppressed in terms of added pressure and gas as it relates to acting on the bolt.

For example, while we initially tested various sub and super loads using SilencerCo’s Velos 7.62, Scythe STM (short and long config), and Sycthe-Ti; once we swapped to their Spectre 9 (smaller design with less internal volume), we had zero issue cycling the most troublesome sub loads and were able to get the bolt to lock back consistently.

For shooters running 5.56 or .223 suppressed, typically he or she will reduce the gas — until enough suppressed shooting starts gunking up the rifle and it becomes necessary to turn the gas back up to get the gun to run.

For .300 Blackout setups, rarely is “turning up the gas” an option. While we mentioned earlier a suppressor providing blowback can help cycle the bolt, it will also dirty up internals far quicker as a result — sort of a double-edged sword, especially over dozens of rounds.

Long story short: Clean .300 Blackout setups regularly, or, at the very least, clean the bolt and chamber and oil the worn strips on the BCG where friction occurs. The smallest changes can make a big difference when trying to get a .300 Blackout SBR or AR pistol to cycle properly.

A lot of gas ports on a .300 Blackout barrel will measure at 0.10 inch. Some shooters may consider drilling out the gas port a fraction at a time, but this can run the risk of chipping the chrome lining of the barrel (should it have one). While this is an option discussed on forums, we advise speaking with a trusted, professional gunsmith before taking a bit to a barrel.

Still, despite interchangeable components on a shorter-barreled .300 Blackout setup, a competent handloader could bypass that process with a perfectly tuned .300 BLK load.

Manufacturers of factory-loaded ammunition adjust their powder charge to remain below the speed of sound (generally accepted as 1,125 fps at sea level) for 16-inch-length barrels. For individuals rocking shorter barrels — and thus less velocity — it is indeed possible to raise that powder charge, thus increasing gas acting on the BCG and still remain subsonic.

Read the full article here