It had been one week since roughly 60,000 service members rushed ashore the sulfurous outcropping that was Iwo Jima.

Despite the island being barely 10 square miles in area, “assault troops,” writes the Naval History and Heritage Command, “were to be subjected to a step-by-step battle of attrition, slowly progressing from one well-defended killing zone to the next.”

American air superiority by this late state of the war left the Japanese ground forces virtually unprotected, forcing them into the earth. On Iwo, a system of mutually supported network of caves, tunnels, concrete pillboxes and fortified strongpoints and artillery positions allowed for the dug in enemy to simply await the Americans.

The honeycombed defensive positions often meant that naval support and Army air power were negligible, meaning that “small teams of Marines — or even individuals — armed with flame throwers, satchel charges and hand grenades (“blow torches and corkscrews”) were those who were instrumental in destroying Japanese strongpoints,” writes the NHHC.

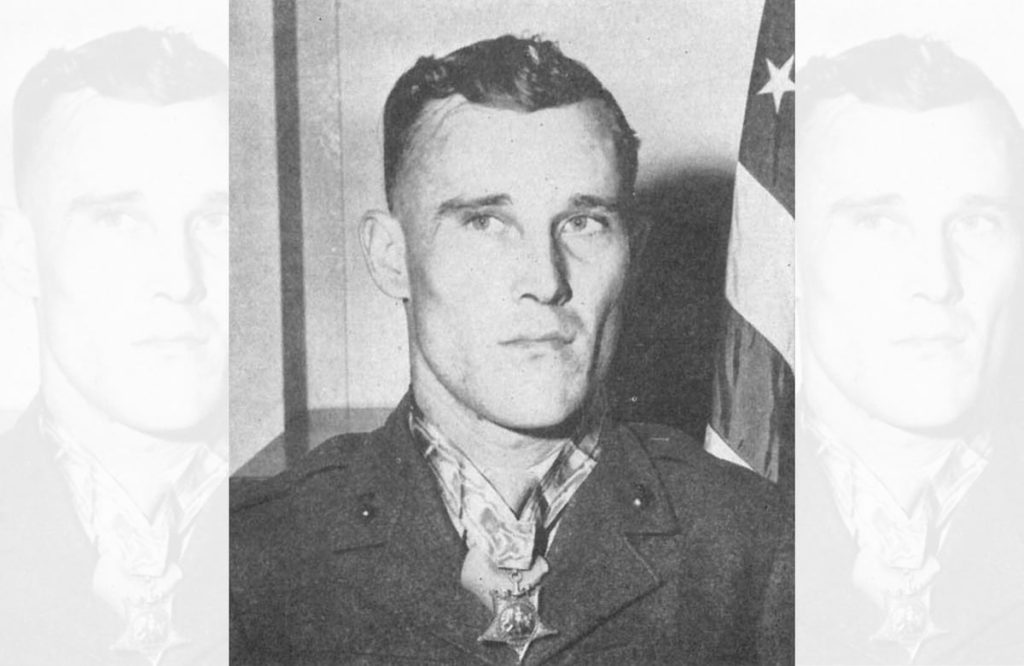

It was within these conditions that Pvt. Wilson “Doug” Watson found himself in.

The 23-year-old son of an Arkansan sharecropper was an automatic rifleman with the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division. He had already seen combat on Bougainville in November 1943 and on Guam in the summer of 1944 before Watson and his men were slated to invade Iwo Jima beginning on Feb. 24, 1945.

Beginning on Feb. 26, Watson and his unit were charged with assaulting a line of fortified bluffs extending north from the western end of Motoyama Airfield No. 2. To reach them, the Marines would have to cross the open runway — and through the killing zone.

“The Ninth faced a heavy curtain of small-arms fire from exceptionally well-concealed positions — so well-concealed, in fact, that the men were unable to locate the source of the fire from within 25 yards of the emplacements,” the regimental historian later reported.

Upon reaching the bluffs, the Marine attack deteriorated into what one witness described in James H. Hallas’s book “Uncommon Valor on Iwo Jima” as “rock fighting — fierce localized struggles for mounds of tumbled boulders, for 100-foot, craggy ridges, for sharp chasms and twisting gullies.”

By the 27th, Watson and his Marines, still pinned down by enemy, struggled to advance more than 15 yards. Casualties began to mount.

It was then that Watson, half running, half crawling, “boldly rushed one pillbox and fired into the embrasure with his weapon, keeping the enemy pinned down singlehandedly until he was in a position to hurl in a grenade and then running to the rear of the emplacement to destroy the retreating Japanese and enable his platoon to take its objective,” according to his Medal of Honor citation.

“Again pinned down at the foot of a small hill, he dauntlessly scaled the jagged incline under fierce mortar and machine-gun barrages and, with his assistant BAR man, charged the crest of the hill, firing from his hip. Fighting furiously against Japanese troops attacking with grenades and knee mortars from the reverse slope, he stood fearlessly erect in his exposed position to cover the hostile entrenchments and held the hill under savage fire for 15 minutes.”

In just a quarter of an hour, Watson managed to kill 60 Japanese, earning the moniker the “One-Man Regiment of Iwo Jima.”

Medically evacuated on March 2 after suffering from a gunshot wound to the neck, Watson was among the 14 men — 11 Marines and three Navy service members — to be awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman on Oct. 5, 1945.

“Battle fatigue,” according to an Oct. 6, 1945, New York Times article, “was still visible on the faces of some of the Marine guard of honor, many of whom had recently returned to this country.”

Discharged from the Marine Corps the following year, Watson enlisted in the U.S. Army working as a mess hall cook and ultimately attaining the rank of staff sergeant. In 1963, however, Watson was charged with desertion after going AWOL from Fort Rucker, Alabama, for four months beginning in October 1962.

“He told me he just got tired of it all,” according to a friend of Watson’s who was interviewed by the Baker City Herald in February 1963. “He said they [the Army] had got his record all messed up. He got teed off, got in his car and drove off.”

The charges were eventually dropped and the Marine-turned-soldier retired in 1966. He died on Dec. 19, 1994, and is buried at Russell Cemetery in Ozone, Arkansas.

Claire Barrett is an editor and military history correspondent for Military Times. She is also a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here