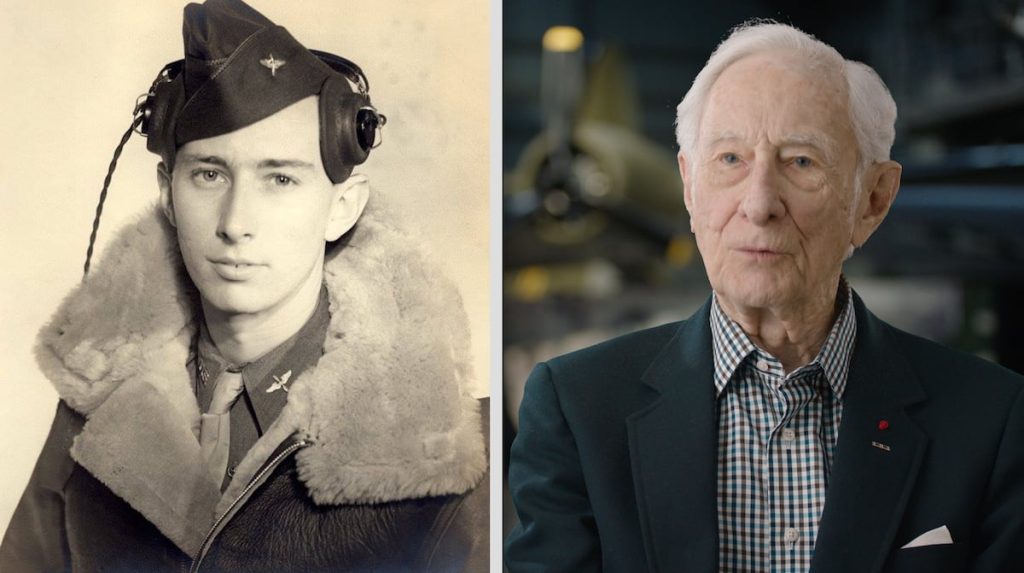

Maj. John “Lucky” Luckadoo, the last surviving B-17 pilot of the Eighth Air Force’s famed “Bloody Hundredth” Bombing Group, died in his home Sept. 1, his family announced. He was 103.

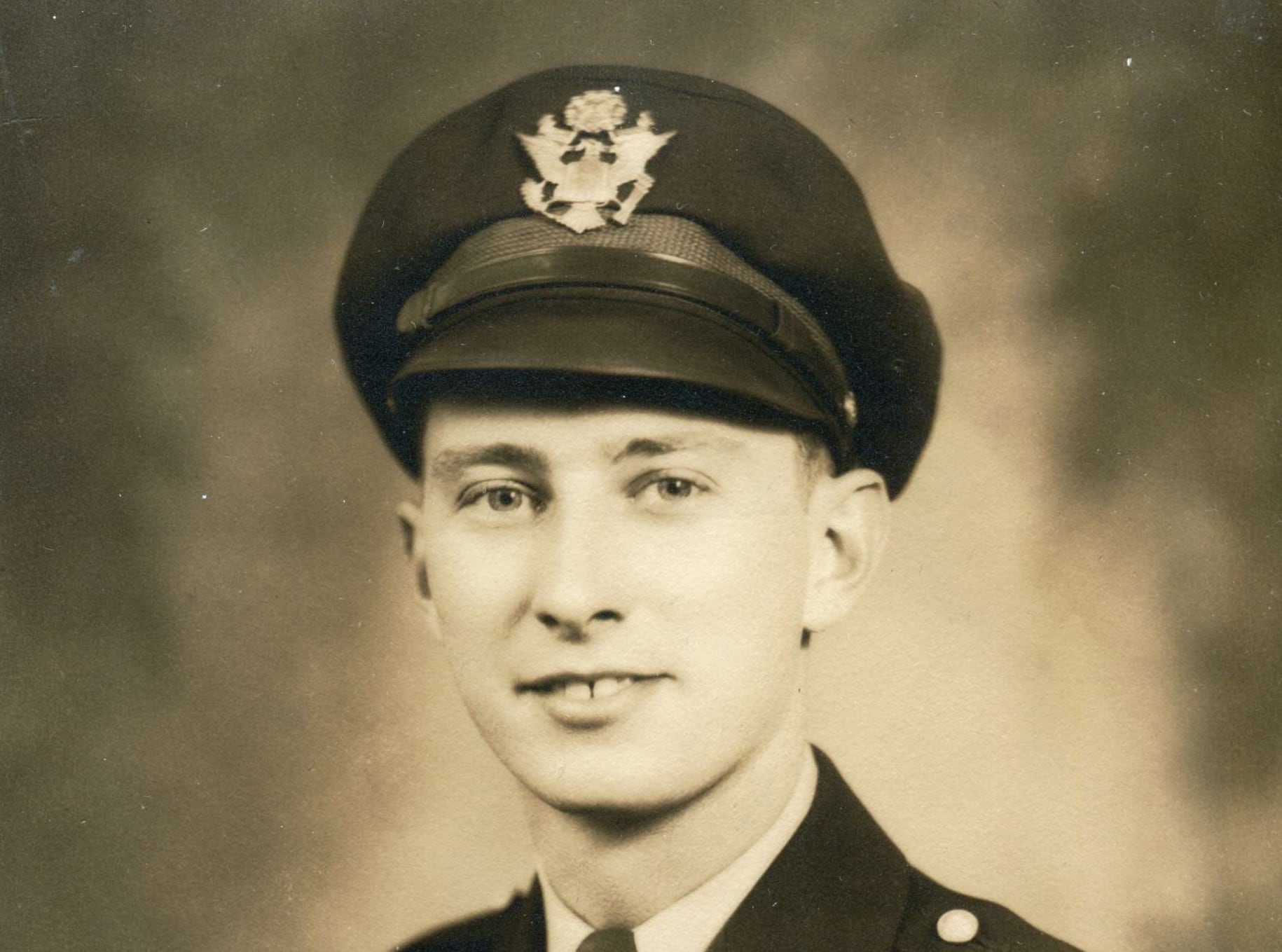

Born March 16, 1922, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Luckadoo would join the U.S. Army Air Forces months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

He was just a wide-eyed 21-year-old lieutenant assigned to the Mighty Eighth’s 100th Bomb Group when he manned the controls and took to the sky for his first bombing mission over Nazi Germany as co-pilot of a famed B-17 Flying Fortress.

The aeronautical revelation at Luckadoo’s fingertips could fly at altitudes of 35,000 feet for up to 2,800 miles. And it did so carrying a hefty bomb payload supplemented by 10 .50-caliber machine guns.

Flying it, however, was deadly. So much so that the odds of a B-17 crewman surviving the 25 missions required to complete a combat tour were only one in four.

Until the 1944 introduction of the P-51 Mustang to the air war over Europe, the B-17’s impressive distance capabilities meant daylight bombing runs over Germany would have to be done without fighter escorts, leaving inexperienced B-17 crews to fend for themselves against the seasoned pilots of the Luftwaffe.

RELATED

What was worse, German anti-aircraft batteries peppered the American bombers with 88mm shells — or “flak” — hurled five miles into the air that would explode within feet of a B-17 flying at its required bombing altitude.

One Flying Fortress crew member went so far as to compare the ever-present threat of shrapnel to Russian roulette.

“You were going to be hit by it,” he said. “It was just a matter of where it would hit you and when.”

Luckadoo recalled the such experiences years ago in an interview with the National World War II Museum, saying the flak was “so thick that you could put your wheels down and taxi on it.”

“Lucky,” a fitting moniker bestowed upon him by his men, would be one of the fortunate few to beat the odds and complete 25 missions, but certainly not before the war left its indelible mark.

On Oct. 8, 1943, Lucky took to the sky for his 22nd mission, one that would be forever etched into his memory.

“We experienced the heaviest anti-aircraft defense that we had ever seen,” he previously told Military Times.

“The Germans had moved in some 300 88mm guns to protect their targets. We had never seen them throw up such a heavy barrage of defenses. Also, what we had never experienced or witnessed before was the fact that their fighters were attacking us through their own flak.”

The Germans’ uncharacteristic tactics Lucky witnessed that day were just getting underway.

“As we turned on the initial point for our bomb run, I noticed out of the corner of my eye that there was this flight of Focke-Wulf 190s that were headed straight for our squadron,” he recalled.

“They fired all the way coming in and of course our gunners were pouring out as much as they could to dissuade them, but they never veered in the slightest. The lead airmen of the fighters actually rammed the ship directly in front of me. It blew it out of formation and they both exploded.”

Lucky was forced to dip the nose of his plane to avoid a midair collision.

“His wingman actually scraped my top turret as he went across. That’s how close they came to ramming me.”

Amidst the exchange, one of Lucky’s engines had been taken out by flak.

Making matters worse, the plexiglass nose of his plane blew out, leaving the pilot and the crew of the unpressurized plane exposed to temperatures of 50-below at 21,000 feet.

“I suffered the only injury — physical injury — of my entire tour on that mission, and that was frostbitten feet,” he said. “They were frozen to the rudder pedals so when I landed I had to land with my heels. I couldn’t even apply the brakes.

“The horror of that mission stayed with me for the rest of my tour.”

By the end of February 1943, half of the crews belonging to the “Mighty Eighth” had been shot down.

Capt. Robert Morgan, pilot of the famed B-17 Memphis Belle, noted that it seemed like each day, airmen would have breakfast with a crew of 10 but dinner with just two.

Morgan and his crew would become the eventual subjects of Oscar-winning director William Wyler’s film, “Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress.”

Lucky, meanwhile, returned to the U.S. in March 1944 and would go on to attend instrument school at Bryan Army Air Field in College Station, Texas, where he would meet his eventual wife, according to the National WWII Museum.

After the war, the G.I. Bill would help Lucky earn a degree from the University of Denver. In his later years he would take on an active role in educating younger generations about the horrors and bravery of the air war over Europe.

Such advocacy led to Luckadoo being awarded in 2021 with The National WWII Museum’s Silver Service Medallion. He would also be the subject of a 2022 book by Kevin Maurer, Damn Lucky: One Man’s Courage During the Bloodiest Military Campaign in Aviation History.

The book, like his nickname, bears a fitting title for one who, throughout his 103 remarkable years, acknowledged the undeniable fortune of longevity after such experiences.

“The truth of the matter is, nobody goes into battle and comes out the same,” Luckadoo said. “You’re a different person with a different perspective, a different psychology. You’re happy to be alive and you don’t really know why, but you realize that you’ve been spared and you just thank your lucky stars you were. You had a guardian angel on your shoulder. It was just a matter of pure luck you survived.

“That’s why they called me ‘Lucky.’ They ought to call me ‘Darn Lucky.’”

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here