The Slovak Republic, commonly called Slovakia, is a land of many names. This piece of earth has been continuously home and habitat to some form of peoples for over a quarter million years. Stretching from the early Paleolithic to modern day, uncountable kings, overlords, and empires planted their flags, changed names and governmental systems, and left indelible marks upon the land.

The current nation iteration began in 1993 after the Velvet Divorce dissolution of Czechoslovakia. The official language is Slovak, a rich mix with at least three main dialects and dozens of regional variations. It also wouldn’t be strange to hear some Hungarian. Or English, Russian, or Roma. Slovakia also has great geographic diversity, especially for its size, and is home to forests, mountains, lakes, and lowlands.

It’s in this space and place that Jaroslav Kuracina, founder of Grand Power, was reared. Grandson of a World War II partisan fighter, Kuracina sketched weapon designs while in military school and then produced his first functional prototype pistol, the Q200, in 1997.

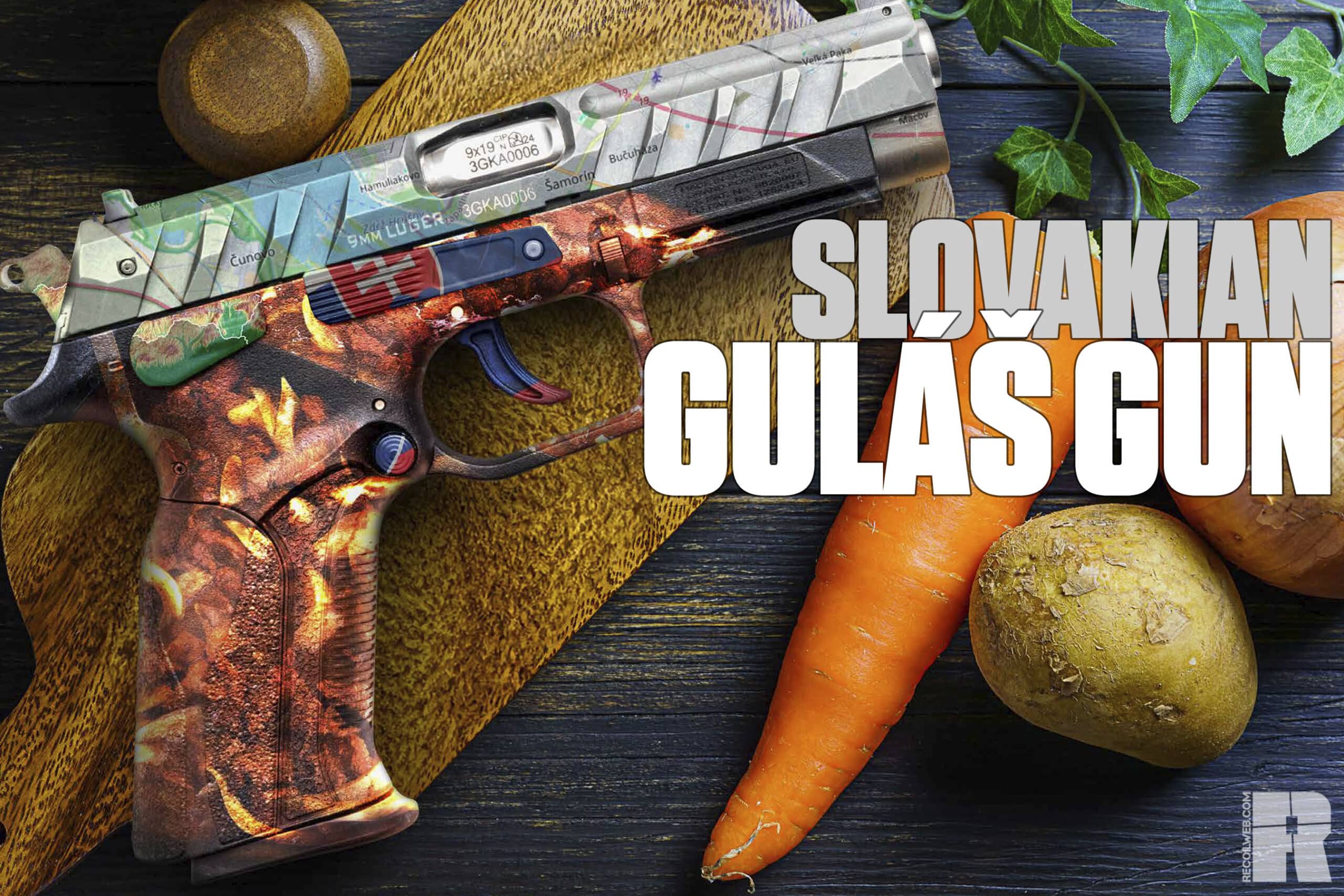

When Americans think of Grand Power, the Stribog subguns are the first thing that come to mind. And indeed, on star-spangled soil they’re the most popular in any form. However, the subject of this article, the K100 Mk23, is direct successor of Grand Power’s origin — and perhaps emblematic of the company and the Slovak Republic as a whole.

Over the years, Grand Power produced a great many pistols with enough designations to demand a decoder ring, but you can trim this long list a bit by separating them by either sporting a striker or having a hammer.

The hammer-fired Grand Power K100 Mk23 is a DA/SA pistol, meaning it’s capable of both cocking and releasing the hammer with one pull (double-action) or simply releasing an already-cocked hammer (single-action). There is no decocking mechanism, so the only way you’re going to have a double-action pull is by manually lowering the hammer or if you have a dud.

Hammer or striker, something that makes a great many Grand Power designs stand out, the K100 Mk23 included, is a rotary-barrel action. American pistols produced in the last century chambered in 9mm and above have overwhelmingly been tilt-barrel Browning actions.

Simple in design and cheap to manufacture, with a Browning action, the muzzle rises and the breech lowers as the slide moves to the rear after firing — hence the “tilt” in the name. A rotary action is theoretically more accurate and has less felt recoil because the barrel only moves linear to the bore and the bore axis itself can be lower. The main rotary actions you’ll see in the States come from Beretta, though the newer Smith & Wesson 5.7 has one too.

Opening up the nondescript plastic clamshell reveals a pistol that looks and feels both familiar and foreign at the same time. The slide is heavily scalloped, the shine of the polished stainless steel barrel peeking from the ejection port and a hammer hanging out at the rear.

The frame is polymer, with a smattering of swoops and stylized lines paired with a tapestry of textures to fit and grip the hand and fingers. Just enough beavertail on the back to keep the hand high and tight. There’s a functional accessory rail up front, allowing easy attachment of full-size lights or lasers.

The controls are fully ambidextrous and mirrored, the plastic safety lever and steel slide stop slim to reduce snagging. The trigger guard is squared off and textured at the front, the magazine release a circular button easy to hit with either hand. The trigger itself is plastic, something we’ve seen plenty with striker-fired guns but not really on anything that has a hammer.

There are three additional backstraps of different sizes in the box to accommodate different mitts. In a world where most pistols come with maybe two magazines, the K100 Mk23 has three unmarked 15-rounders with bright red followers. There are also four plastic optic plates to accommodate the most popular options. The inclusion of a spare set of front sites was equally encouraging and concerning until we realized they were different heights and not solely spares.

If you have a pistol that can accept an optic, the first thing you should do is put an optic on it. These days even the cheap optics are reasonably durable and have a battery life that lasts years, so it makes little sense to limit yourself. The Grand Power K100 Mk23 comes ready to go with four plates for Noblex universal, Trijicon RMR, C-More STS2, and Shield RMSc.

Most of the time included optic plates would be made of metal, but here they are polymer. We admit this may not inspire confidence, but we’ve seen the same successfully done with Arex pistols. The plate screws onto the slide, and the optic attaches to the plate via recessed nuts. What we will say about the polymer plates is that you definitely don’t want to put a plastic optic on them, and you want your screws to be the right height.

There are two unlabeled sets of screws, one M3 and another M4. Unless you get lucky, you might end up at a hardware store finding the right fasteners (or spend $20 on the Swampfox Ultimate Screw Pack). If the screw is too long, it’ll flex the plate; too short and it won’t work at all. We got lucky and a Leupold DeltaPoint Pro dropped right in.

A SureFire X300U-B serves as a weapon-mounted light.

The included manual covers all eight of Grand Power’s Mk23 pistols. Unlike many manuals, you’re going to want to keep this one at least for a bit. Field stripping and reassembly is atypical, and you’ll need the reference the first few times. After removing the magazine and clearing, to disassemble, you need to pull the slide all the way back, pull down on the takedown levers, and pull back just a bit more in order to lift the slide off the rails.

It’s here you’ll encounter a little more weirdness. Normally when we think of a captured guide rod, it’s of a recoil spring assembly that stays all in one unit, like a Glock or a SIG. Here, the recoil spring isn’t captive but the guide rod is attached to the frame. This means it’s a snap to swap springs, but it does complicate an already-complicated disassembly/assembly procedure.

Assembly is close to the reverse except the barrel needs to be forward. And it’s more difficult because you have to ensure the guide rod lines up, and you’re fighting the recoil spring for a longer period of time. It feels like a second pair of hands is required, but we found it easiest to brace the backstrap on a knee as we pulled back the slide with one hand and pulled down the takedown levers with the other. You’ll know the slide can be lifted off when the furthest-forward rear slide scallop lines up with the beavertail.

If you’re having a difficult time, try removing the recoil spring for a trial run just so you get used to where everything needs to line up.

At the end of the day, there are two ways you can approach this: practice fieldstripping the Grand Power K100 Mk23 until you can do it quickly and consistently, or simply perform routine maintenance without removing the slide. Though the latter seems like a bit of a cop-out, you really can do what you need to do (namely: wipe off gunk and lube moving parts) without having to remove the slide at all. If you’re going to carry and shoot this one regularly, we recommend putting in the reps.

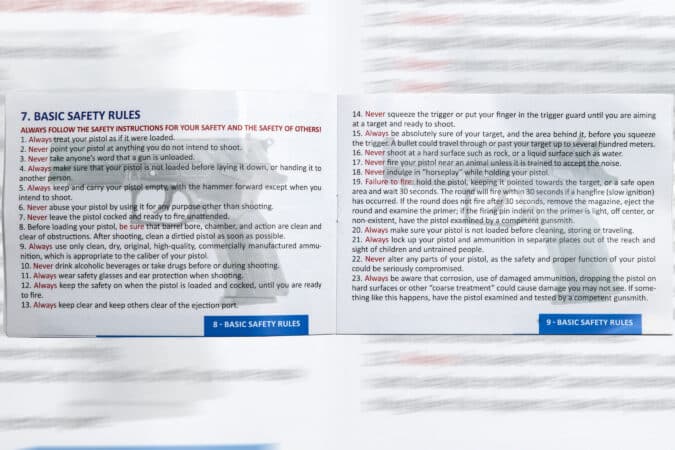

For another notch in the quirks column, pages 8 and 9 cover basic firearm safety rules. You’re probably acquainted with four, but how about 23 of them? We suspect something got lost in translation along the way.

One of the purported benefits of a rotary-barrel setup is reduced recoil, and we tried this for ourselves using the vaunted Bag of Random. If you want to test if a gun will run with a variety of ammo, load up some party mags that taste the full rainbow of rounds — the Bag of Random is a continually changing and evolving sack of 9mm ammunition.

It has everything from pissweak foreign ammunition that’s long been banned from importation, extra-powerful loads meant for machine guns, modern defensive offerings, dumb discontinued designs, along with range training rounds that span the spectrum of grain weight and bullet shape.

The Grand Power K100 Mk23 ate all of them without issue, the action of the slide was smooth, with recoil pushing directly back into the hand. The main difference isn’t the kick but the muzzle report and flash firing from the end, the strong stuff giving brighter bangs and the weaker meeker. It’s like the K100 Mk23 averages them all out, and at least with this one the claims of reduced recoil are absolutely true.

The double-action is pretty good, but it really excels with the shorter travel and lighter pull of the single-action. The plastic trigger gives us pause, but only time will tell on that one. The extra irons weren’t needed, but if the front fell off, we wouldn’t be replacing it anyway. Regarding claims of increased accuracy versus a Browning action? That one is still up in the air, but essentially all 21st century pistols, regardless of action, will print better patterns than the one pulling the trigger.

All in all, it’s no surprise that Grand Power made a competition model, the X-CALIBUR (real spelling, remember: Slovakia), with the same action but having a skeletonized slide, enhanced controls, and a match-grade fluted barrel.

Because there’s no decocker, the only way to release the hammer is with the trigger. Lowering the hammer while one is in the chamber can be dicey and dangerous, and it’s not something that should be performed casually. If you’re lowering the hammer manually, the muzzle must must must be pointed in a safe direction while you do so. Ideally, this is performed on the range, but a 5-gallon bucket of sand or mound of dirt will also suffice.

As to why? It’s not uncommon to carry in double-action mode for reasons of safety (which is a bit comical as slippery hands can result in a bang). This is for two reasons: The double-action pull is both longer and heavier, making it more difficult to inadvertently pull and acts as a secondary safety. Also, especially important for those carrying up front and appendix, your thumb can press on the back of the hammer while holstering to prevent a negligent discharge.

Additionally, in some gun games it’s part of the rules: USPSA requires fully lowering the hammer on DA/SA pistols (rule 8.1.2.3) in order to compete in their Production division. There’s no safe or sound reason for this ruling, and it explains the design of “competition hammers,” but here we are and there it is.

In order to fully lower the hammer, as in lay it against the firing pin, you have to keep the trigger pulled during the entire operation. There’s a “half cock” position where you have the same double-action pull but the hammer doesn’t rest on the firing pin — this isn’t gun-gamer legal, but it is the way we’d recommend rolling if you’re going to lower the hammer.

This is something that should be practiced dry several times before you try it live.

Here we’re not talking about holsters and where to put them on your body, but the condition of the gun. You essentially have a combination of hammer and safety positions with some different considerations. These are all assuming that you’ll be carrying with one in the chamber. If you’re going to run on empty, we recommend reading “Carrying with an Empty Chamber” in CONCEALMENT Issue 33 first.

Hammer Fully Lowered

In this position, the hammer is pressed on the firing pin, and please note there’s no firing pin safety. This isn’t to say that it’s likely this will be a problem in the case of a drop or fall, but it simply doesn’t seem like a worthy risk. Furthermore, the safety appears to work in this position, but actually doesn’t; when you pull the trigger, it just drops down.

Only do this one if you have to for gun games with silly rules.

Hammer Half-Cocked

Here the hammer doesn’t touch the firing pin and the safety is actually functional. It’s noteworthy that when the safety is engaged at half-cock, the slide is locked in place and the hammer cannot be manipulated. Many opt for running without the safety at half-cock, and we can’t blame them.

There’s a lot of utility to the half-cock position.

Hammer Fully Cocked

This one is easy and automatic — as soon as you rack a round into the chamber or crank one off, the hammer will automatically be in this position. Unlike the half-cock, when the safety is engaged the slide moves freely for administrative actions.

If you’re going to carry with the hammer fully cocked, to go without the safety engaged is tempting fate in a stupid way.

Something that becomes obvious once you start fingering foreign firearms rather than those solely sold in the States is that there can be decidedly different design cultures. Like going on vacation in Eastern Europe, some things are familiar but are a bit weirder and cheaper than you’d like or expect.

The Grand Power K100 Mk23 is a lot of things, but boring ain’t one of them. It’s a delight to shoot. The K100 has plenty of personality, and like anything with personality, there are some oddities. If you take a step back and squint, the pistol can look like a piecemeal of many others. But the reality is that it’s not parts and pieces glommed together, but instead a slow simmer of a great many cultures coalescing in one pot.

What else can you expect from a land that’s had so many names?

Read the full article here