On September 11, 2025, a three-judge panel from the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral arguments in the controversial case of United States v. Matthew Hoover and Kristopher Ervin—a case that’s drawn national attention from gun rights advocates and legal scholars alike.

Background: The AutoKeyCard and the Charges

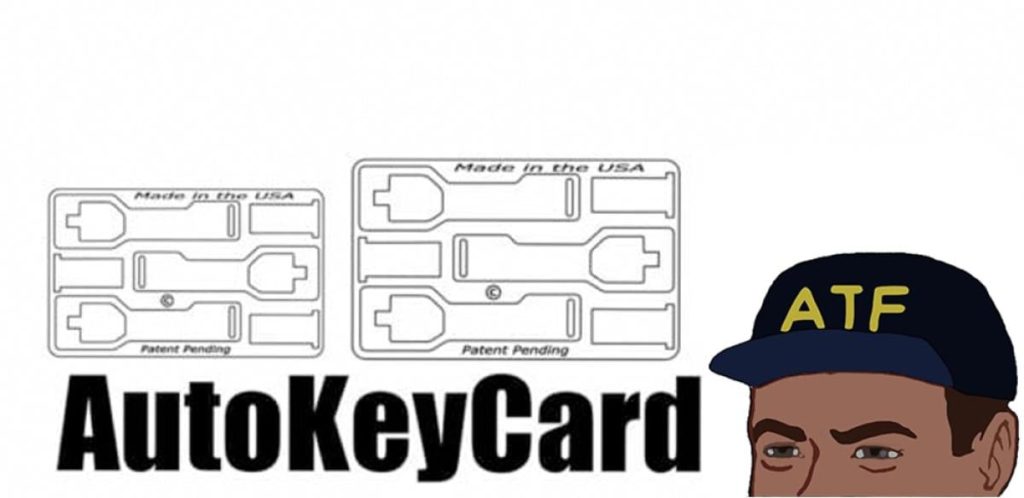

Kristopher Ervin designed and sold the AutoKeyCard, a metal card etched with the outline of a lightning link—a device that, when properly machined and paired with the right AR-15 bolt carrier group, can simulate full-auto fire. According to Ervin, the product was meant to be a political statement against gun control, not a functional firearm component.

Matthew Hoover, better known for his CRS Firearms YouTube channel, promoted the AutoKeyCard on his platform but was not involved in its manufacture or sales. He did, however, launch a fundraiser for Ervin’s legal defense after the ATF came knocking. Prosecutors claimed that the fundraiser itself was part of a broader conspiracy to resume AutoKeyCard sales.

Both men were convicted in 2023 of trafficking in machine guns, even though the District Court barred any mention of the Second Amendment in their defense and instructed the jury that the AutoKeyCard was a machine gun under the law.

Appeal Arguments in the Eleventh Circuit

During the appeal, Valerie Lennon represented Ervin, while Matthew Larosiere represented Hoover. The three-judge panel included:

- Chief Judge William Pryor (George W. Bush appointee),

- Judge Nancy Abudu (Joe Biden appointee, former SPLC attorney),

- Judge Elizabeth Branch (Donald Trump appointee).

AutoKeyCard vs. Everyday Objects

Lennon opened with a powerful visual: holding up an Apple titanium credit card and comparing it to the AutoKeyCard. Judge Pryor challenged that comparison immediately, arguing that the AutoKeyCard was specifically etched to resemble a machine gun part.

She countered that even under the federal definition of a “machine gun conversion device,” a single metal card with etchings doesn’t meet the threshold for being a combination of parts. Judge Pryor retorted: “The jury thought otherwise.”

Rule of Lenity and First Amendment Concerns

When Lennon invoked the rule of lenity—which favors the defendant when a statute is ambiguous—Judge Pryor tried to shut it down, claiming ambiguity doesn’t equate to vagueness. Lennon stood her ground, arguing that the law doesn’t cover precursor materials.

Judge Abudu raised the Vanderstok case, where the Supreme Court ruled that unfinished firearm kits could be considered firearms. Lennon responded that completing an AutoKeyCard into a functioning lightning link requires significantly more effort and additional components than finishing a Polymer80 frame.

Pryor also questioned whether Hoover’s First Amendment rights were relevant, suggesting that “speech doesn’t protect crime,” seemingly accusing Hoover’s YouTube content of inciting illegal behavior.

Larosiere: “A Drawing Isn’t a Machine Gun”

When it was Larosiere’s turn to argue for Hoover, he came out swinging: “It’s absurd to suggest a drawing on a card constitutes a machine gun.”

Pryor pushed back, saying the drawing was etched to scale. Larosiere reminded the court that ATF Firearms Examiner Cody Toy had to cut outside the lines and still couldn’t get the device to function properly. He also emphasized that one etched card does not meet the legal standard for a “combination of parts.”

Abudu challenged this, implying it was more than just a drawing. When asked where the legal line is drawn, Larosiere couldn’t define an exact threshold—but was clear that it must be more than a single etched card.

Government Response: All About “Intent”

Federal prosecutor Gregory Kehoe leaned hard on Hoover’s YouTube commentary, especially a line about “scratching the full-auto itch,” claiming it was proof of criminal intent.

Kehoe likened the AutoKeyCard to IKEA furniture—a kit you assemble with instructions—saying it didn’t matter that it wasn’t fully functional. What mattered, he argued, was intent.

Kehoe also tried to downplay Firearms Examiner Toy’s testimony, calling him a novice—conveniently omitting that Toy is a former Marine Corps armorer. Larosiere pointed this out during the rebuttal.

When Judge Pryor asked Kehoe the same question he had asked the defense—at what point does a piece of metal become a machine gun part?—Kehoe had no answer.

What’s Next?

There’s no set timeline for the Eleventh Circuit’s ruling. If the appeal is denied, Hoover and Ervin could request an en banc hearing or take their case directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Read the full article here